3D Printing

When I was eight years old my parents bought me my first computer and it immediately felt like an infinite world of possibilities had suddenly been unlocked. The chance to write programs meant a chance to turn any potentially imaginable thing into reality. Although I didn't realise it at the time, the feeling had basis in truth. The computer I had when I was eight was capable of running any algorithm that could be written on a computer now, and although the graphics were limited to a palette of only 8 colours and a resolution of 640 x 256, it was the limits of my imagination that were the more obvious.

This week I took delivery of my first ever 3D printed model. The experience of conjuring a full 3D object through from imagination to physical reality is intoxicating, and the freedom that 3D printing technology allows makes me slightly giddy in the same way my introduction to computers did 25 years ago. Either that, or it's the geeky feeling that someone just invented the Star Trek replicator.

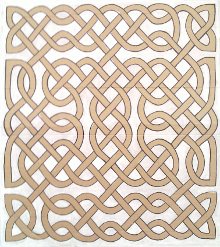

The particular object I had printed is a Celtic knot that started its life 10 years ago when Joanna and I bought the book

"How to Draw Celtic Knotwork - A Practical Handbook" by

Andy Sloss. The book provides a simple but ingenious method for drawing Celtic knots. The really neat thing about the technique is that all of the constraints are built into the process. As long as you follow the process correctly, everything that results is guaranteed to be a well-formed Celtic knot.

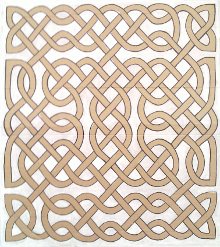

Joanna and I used the technique to create together a huge Celtic Knot pattern that we hung on the wall for quite a number of years. You can also give the method a try using my

Celtic Knot web app that does the same thing.

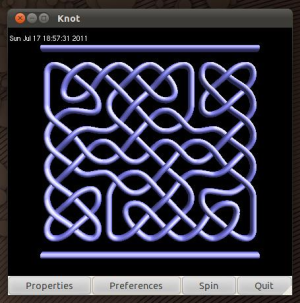

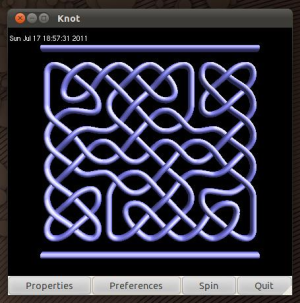

Another nice feature of Andy Sloss's process is that it can be generalised from the two dimensions described in the book to higher dimensionality using similar rules. I won't go in to the details here – they'll save for another time – but the generalisation is pretty straightforward. Over the last few months I've been working on a program to allow 3D Celtic Knots to be rendered using Open GL. Most of the work for this was done while Joanna and I were on holiday in Tuscany. Joanna managed to find what felt like the most secluded holiday home in Italy (no phone line, mobile phone signal, TV or other people). It turns out that tranquillity and beautiful scenery make for a great programming environment!

The program will generate standard 2D knots as well as 3D knots. Unfortunately the 3D variety look rather messy and difficult to interpret when they're viewed on screen. Still, the idea was to get it printed out in 3D, so the question of whether this would be true for the physical object too intrigued me.

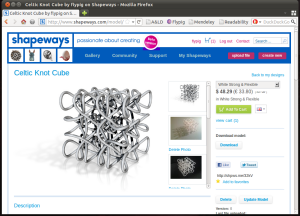

To actually do the printing I found an amazing company called

Shapeways, which is based in the US and Netherlands. They provide on-demand 3D printing of any object you upload to their website as a 3D mesh. However, to actually get the thing to print there are a few rules that have to be followed: the object has to be watertight, manifold and with consistent normals. For this particular model it was most tricky ensuring the model was manifold.

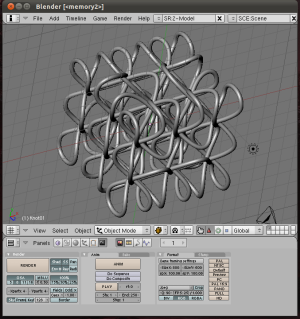

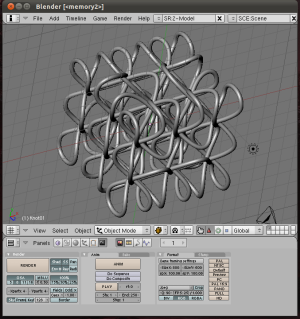

To perform this check I output the model in Stanford PLY format (which is nice and conceptually simple; very different from other modelling languages like Collada) and loaded the result into blender. Blender offers the ability to check whether the object is manifold or not, highlighting the areas which are a problem. It took a good deal of effort to persuade my program to output manifold models, but after much headscratching and a fair bit of frustration it eventually got there. Loading the model into Blender also allowed me to scale it to the right size for printing.

Blender's an amazing program, and I hear very good things about it, but the interface really does seem to be a law unto itself. It feels like everything was deliberately switched round and all of the buttons given obscure textual acronyms just to be confusing. I'm sure if you use it a lot it becomes second nature, but personally I struggle with it.

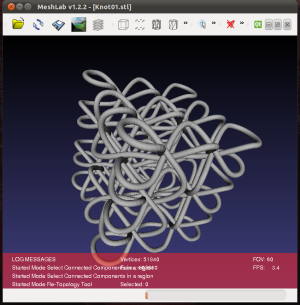

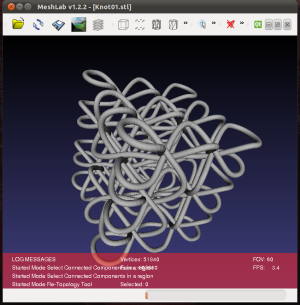

Shapeways also recommends a program called MeshLab to do final checking of the mesh. Luckily everything seemed to be in order, and the results from MeshLab were consistent with those from Blender, leaving me feeling confident that everything would be in order.

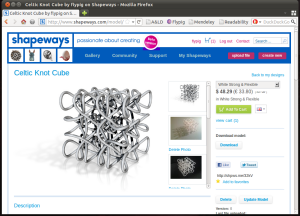

I was amazed when the mesh uploaded to Shapeways perfectly on the first attempt. Shapeways even provide you with a nice instant render and rotating 3D view to show what the final object should end up like. What's also great about the Shapeways site is that you can even let other people print out copies of your mesh, providing you with an instant shop that you can sell your creations from. It's an amazing concept.

There's no stock, they're printed out on-demand, and items can be automatically personalised since each one is printed out individually.

With this technology the process of mass-production has truly come full-circle. Before mass-production everything was made by hand; everything was bespoke and made-to-order. Mass-production widened ownership, but also removed personality. Finally with 3D printing items can be copied, tailored and constructed on-demand. The barriers to producing complicated crafted objects just disappeared. It really does feel like a step into the future.

On Friday night I finally received the printed version of my 3D Celtic knot, and the quality of the printing is beyond my expectations. Although it has quite delicately intertwining paths, the object is made from a nylon material and is quite sturdy. Apparently it's printed by shooting lazers (yes that's right:

shooting lazers!) into a nylon dust that causes it to solidify, meaning that you really can practically print any shape – even objects with moving gears pre-assembled!

To the right is a photo of the finished object. The great thing is that by changing the parameters of the program a whole variety of different knots can be created of different sizes, thicknesses, shapes and patterns, and any of them could be generated in physical form with just a few clicks of the mouse.

Technologies that suddenly offer limitless possibilities beyond those available before them are a rare thing, but like computing before it, I can't help feeling 3D printing promises to falls into this category. It feels like a privilege to be able to experience the shift first hand. But of course that's the whole point. If 3D printing really can revolutionise bespoke on-demand creation beyond the mass-production of today, it absolutely has to be something that's accessible to everyone.

When I was eight years old my parents bought me my first computer and it immediately felt like an infinite world of possibilities had suddenly been unlocked. The chance to write programs meant a chance to turn any potentially imaginable thing into reality. Although I didn't realise it at the time, the feeling had basis in truth. The computer I had when I was eight was capable of running any algorithm that could be written on a computer now, and although the graphics were limited to a palette of only 8 colours and a resolution of 640 x 256, it was the limits of my imagination that were the more obvious.

When I was eight years old my parents bought me my first computer and it immediately felt like an infinite world of possibilities had suddenly been unlocked. The chance to write programs meant a chance to turn any potentially imaginable thing into reality. Although I didn't realise it at the time, the feeling had basis in truth. The computer I had when I was eight was capable of running any algorithm that could be written on a computer now, and although the graphics were limited to a palette of only 8 colours and a resolution of 640 x 256, it was the limits of my imagination that were the more obvious.

This week I took delivery of my first ever 3D printed model. The experience of conjuring a full 3D object through from imagination to physical reality is intoxicating, and the freedom that 3D printing technology allows makes me slightly giddy in the same way my introduction to computers did 25 years ago. Either that, or it's the geeky feeling that someone just invented the Star Trek replicator.

The particular object I had printed is a Celtic knot that started its life 10 years ago when Joanna and I bought the book "How to Draw Celtic Knotwork - A Practical Handbook" by Andy Sloss. The book provides a simple but ingenious method for drawing Celtic knots. The really neat thing about the technique is that all of the constraints are built into the process. As long as you follow the process correctly, everything that results is guaranteed to be a well-formed Celtic knot.

Joanna and I used the technique to create together a huge Celtic Knot pattern that we hung on the wall for quite a number of years. You can also give the method a try using my Celtic Knot web app that does the same thing.

This week I took delivery of my first ever 3D printed model. The experience of conjuring a full 3D object through from imagination to physical reality is intoxicating, and the freedom that 3D printing technology allows makes me slightly giddy in the same way my introduction to computers did 25 years ago. Either that, or it's the geeky feeling that someone just invented the Star Trek replicator.

The particular object I had printed is a Celtic knot that started its life 10 years ago when Joanna and I bought the book "How to Draw Celtic Knotwork - A Practical Handbook" by Andy Sloss. The book provides a simple but ingenious method for drawing Celtic knots. The really neat thing about the technique is that all of the constraints are built into the process. As long as you follow the process correctly, everything that results is guaranteed to be a well-formed Celtic knot.

Joanna and I used the technique to create together a huge Celtic Knot pattern that we hung on the wall for quite a number of years. You can also give the method a try using my Celtic Knot web app that does the same thing.

Another nice feature of Andy Sloss's process is that it can be generalised from the two dimensions described in the book to higher dimensionality using similar rules. I won't go in to the details here – they'll save for another time – but the generalisation is pretty straightforward. Over the last few months I've been working on a program to allow 3D Celtic Knots to be rendered using Open GL. Most of the work for this was done while Joanna and I were on holiday in Tuscany. Joanna managed to find what felt like the most secluded holiday home in Italy (no phone line, mobile phone signal, TV or other people). It turns out that tranquillity and beautiful scenery make for a great programming environment!

The program will generate standard 2D knots as well as 3D knots. Unfortunately the 3D variety look rather messy and difficult to interpret when they're viewed on screen. Still, the idea was to get it printed out in 3D, so the question of whether this would be true for the physical object too intrigued me.

Another nice feature of Andy Sloss's process is that it can be generalised from the two dimensions described in the book to higher dimensionality using similar rules. I won't go in to the details here – they'll save for another time – but the generalisation is pretty straightforward. Over the last few months I've been working on a program to allow 3D Celtic Knots to be rendered using Open GL. Most of the work for this was done while Joanna and I were on holiday in Tuscany. Joanna managed to find what felt like the most secluded holiday home in Italy (no phone line, mobile phone signal, TV or other people). It turns out that tranquillity and beautiful scenery make for a great programming environment!

The program will generate standard 2D knots as well as 3D knots. Unfortunately the 3D variety look rather messy and difficult to interpret when they're viewed on screen. Still, the idea was to get it printed out in 3D, so the question of whether this would be true for the physical object too intrigued me.

To actually do the printing I found an amazing company called Shapeways, which is based in the US and Netherlands. They provide on-demand 3D printing of any object you upload to their website as a 3D mesh. However, to actually get the thing to print there are a few rules that have to be followed: the object has to be watertight, manifold and with consistent normals. For this particular model it was most tricky ensuring the model was manifold.

To perform this check I output the model in Stanford PLY format (which is nice and conceptually simple; very different from other modelling languages like Collada) and loaded the result into blender. Blender offers the ability to check whether the object is manifold or not, highlighting the areas which are a problem. It took a good deal of effort to persuade my program to output manifold models, but after much headscratching and a fair bit of frustration it eventually got there. Loading the model into Blender also allowed me to scale it to the right size for printing.

To actually do the printing I found an amazing company called Shapeways, which is based in the US and Netherlands. They provide on-demand 3D printing of any object you upload to their website as a 3D mesh. However, to actually get the thing to print there are a few rules that have to be followed: the object has to be watertight, manifold and with consistent normals. For this particular model it was most tricky ensuring the model was manifold.

To perform this check I output the model in Stanford PLY format (which is nice and conceptually simple; very different from other modelling languages like Collada) and loaded the result into blender. Blender offers the ability to check whether the object is manifold or not, highlighting the areas which are a problem. It took a good deal of effort to persuade my program to output manifold models, but after much headscratching and a fair bit of frustration it eventually got there. Loading the model into Blender also allowed me to scale it to the right size for printing.

Blender's an amazing program, and I hear very good things about it, but the interface really does seem to be a law unto itself. It feels like everything was deliberately switched round and all of the buttons given obscure textual acronyms just to be confusing. I'm sure if you use it a lot it becomes second nature, but personally I struggle with it.

Shapeways also recommends a program called MeshLab to do final checking of the mesh. Luckily everything seemed to be in order, and the results from MeshLab were consistent with those from Blender, leaving me feeling confident that everything would be in order.

I was amazed when the mesh uploaded to Shapeways perfectly on the first attempt. Shapeways even provide you with a nice instant render and rotating 3D view to show what the final object should end up like. What's also great about the Shapeways site is that you can even let other people print out copies of your mesh, providing you with an instant shop that you can sell your creations from. It's an amazing concept.

Blender's an amazing program, and I hear very good things about it, but the interface really does seem to be a law unto itself. It feels like everything was deliberately switched round and all of the buttons given obscure textual acronyms just to be confusing. I'm sure if you use it a lot it becomes second nature, but personally I struggle with it.

Shapeways also recommends a program called MeshLab to do final checking of the mesh. Luckily everything seemed to be in order, and the results from MeshLab were consistent with those from Blender, leaving me feeling confident that everything would be in order.

I was amazed when the mesh uploaded to Shapeways perfectly on the first attempt. Shapeways even provide you with a nice instant render and rotating 3D view to show what the final object should end up like. What's also great about the Shapeways site is that you can even let other people print out copies of your mesh, providing you with an instant shop that you can sell your creations from. It's an amazing concept.

There's no stock, they're printed out on-demand, and items can be automatically personalised since each one is printed out individually.

With this technology the process of mass-production has truly come full-circle. Before mass-production everything was made by hand; everything was bespoke and made-to-order. Mass-production widened ownership, but also removed personality. Finally with 3D printing items can be copied, tailored and constructed on-demand. The barriers to producing complicated crafted objects just disappeared. It really does feel like a step into the future.

There's no stock, they're printed out on-demand, and items can be automatically personalised since each one is printed out individually.

With this technology the process of mass-production has truly come full-circle. Before mass-production everything was made by hand; everything was bespoke and made-to-order. Mass-production widened ownership, but also removed personality. Finally with 3D printing items can be copied, tailored and constructed on-demand. The barriers to producing complicated crafted objects just disappeared. It really does feel like a step into the future.

On Friday night I finally received the printed version of my 3D Celtic knot, and the quality of the printing is beyond my expectations. Although it has quite delicately intertwining paths, the object is made from a nylon material and is quite sturdy. Apparently it's printed by shooting lazers (yes that's right: shooting lazers!) into a nylon dust that causes it to solidify, meaning that you really can practically print any shape – even objects with moving gears pre-assembled!

To the right is a photo of the finished object. The great thing is that by changing the parameters of the program a whole variety of different knots can be created of different sizes, thicknesses, shapes and patterns, and any of them could be generated in physical form with just a few clicks of the mouse.

Technologies that suddenly offer limitless possibilities beyond those available before them are a rare thing, but like computing before it, I can't help feeling 3D printing promises to falls into this category. It feels like a privilege to be able to experience the shift first hand. But of course that's the whole point. If 3D printing really can revolutionise bespoke on-demand creation beyond the mass-production of today, it absolutely has to be something that's accessible to everyone.

On Friday night I finally received the printed version of my 3D Celtic knot, and the quality of the printing is beyond my expectations. Although it has quite delicately intertwining paths, the object is made from a nylon material and is quite sturdy. Apparently it's printed by shooting lazers (yes that's right: shooting lazers!) into a nylon dust that causes it to solidify, meaning that you really can practically print any shape – even objects with moving gears pre-assembled!

To the right is a photo of the finished object. The great thing is that by changing the parameters of the program a whole variety of different knots can be created of different sizes, thicknesses, shapes and patterns, and any of them could be generated in physical form with just a few clicks of the mouse.

Technologies that suddenly offer limitless possibilities beyond those available before them are a rare thing, but like computing before it, I can't help feeling 3D printing promises to falls into this category. It feels like a privilege to be able to experience the shift first hand. But of course that's the whole point. If 3D printing really can revolutionise bespoke on-demand creation beyond the mass-production of today, it absolutely has to be something that's accessible to everyone.

Comments

Uncover Disqus comments